By Tierra Monique Sydnor

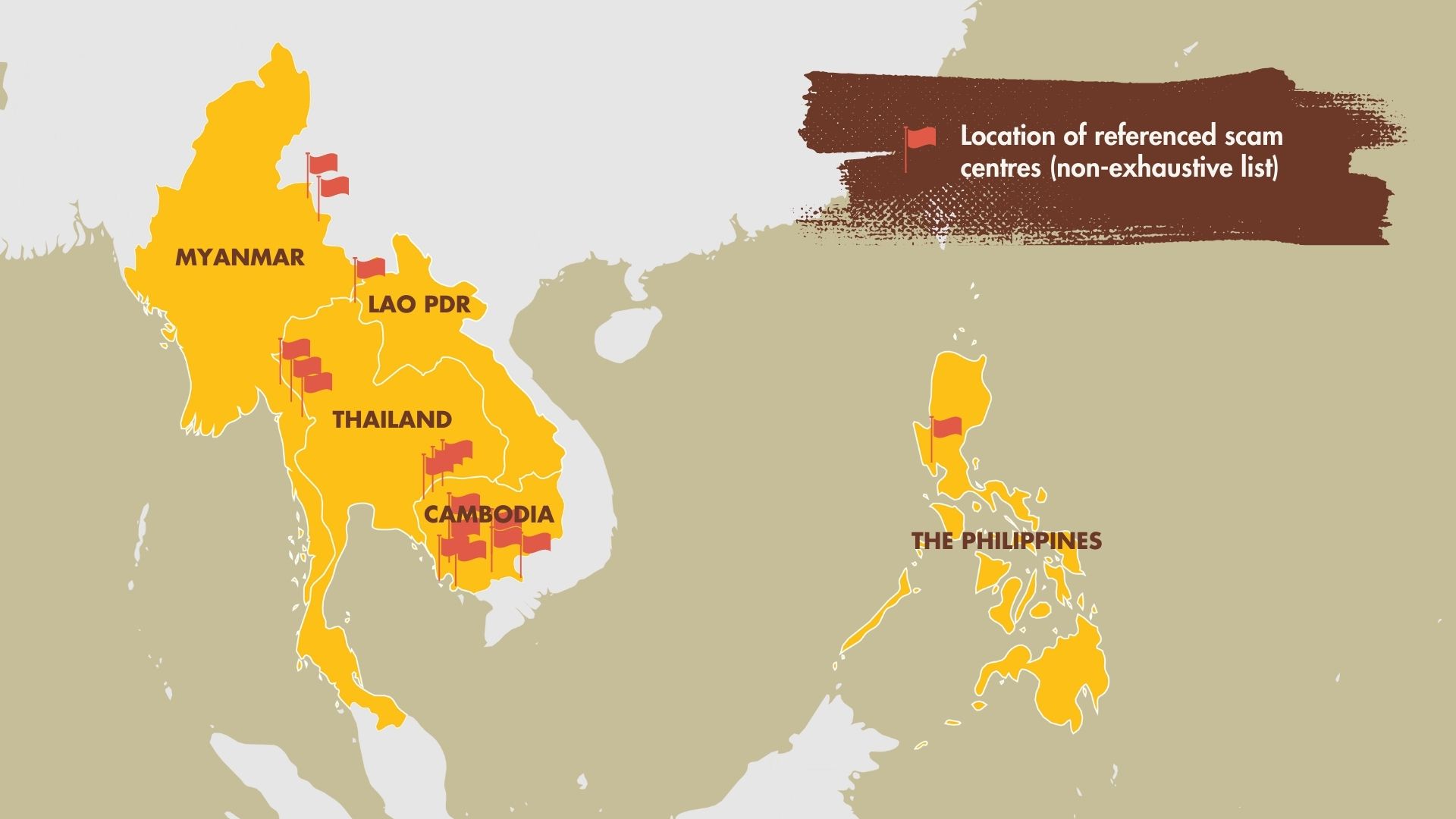

Scam centers in Southeast Asia are doing more than committing fraud and human rights violations; they integrate into the region’s longstanding transnational crime landscape, encompassing drug trafficking, human trafficking, arms smuggling, and related illicit activities that erode economic and political stability within the region. Scam centers are large, organized criminal compounds in Southeast Asia where trafficked victims are forced to work long hours running online fraud schemes such as fake investments, romance scams, and phishing. These centers trap workers, many from different countries, by holding passports and using violence to ensure compliance all while profiting from global cyber fraud and human trafficking networks.

Scam centers across Southeast Asia have become a critical threat to regional stability and governance, generating over $64 billion annually through various online fraud schemes. These illicit operations thrive on a foundation of weak governance and systemic corruption; fueling a shadow economy deeply intertwined with transnational criminal networks. The permissiveness towards scam centers is not an accidental byproduct of local conditions but a willful political choice made by certain actors who benefit from corruption and complicity. This choice risks long-term damage to regional integration, trust between nations, and cooperation across the Indo-Pacific

Scam centers are more than stand-alone criminal hubs; they feed into the broader illicit economy alongside human trafficking, which generates approximately $62 billion annually in the Asian-Pacific. Due to the clandestine nature of the scam centers, the number of people trafficked is difficult to estimate. In 2023 it was estimated that at least 100,000 in Cambodia were forcibly involved in online scams. In 2025, the number has been estimated at 150,000 people. In Cambodia, scam centers may compose as much as half of the national GDP, exposing a dangerous economic dependency on these illegal activities. Such dependence is sustained by corruption and complicity among government officials and private actors. This weakens rule of law and public trust throughout Southeast Asia.

The region’s escalating scam centers are not only a major criminal enterprise but are also fueling regional tensions and undermining trust among Southeast Asian nations. While Cambodia hosts more than 50 scam centers, Thailand plays a different role as a major transit hub for human trafficking victims recruited to scam centers.The increased concern about trafficking and scam centers have been heightened after a Chinese actor was trafficked through Thailand to a scam center in Myanmar. Since, Bangkok has faced rising pressure both domestically and internationally to crack down on scam centers. On December 27th 2025, Thailand and Cambodia entered a second ceasefire, brokered by Malaysia and the United States, that is already on shaky ground. Thailand bombed several Cambodian casino and hotel complexes, claiming that they functioned as scam centers and as military operations by the Cambodian military. While the latter is unconfirmed, this conflict highlights how scam centers have led to increased tensions and border issues within the region.

As illicit funds from these centers flow into militias, drug trafficking, and other transnational crimes, fears of broader security threats grow. This makes it increasingly urgent for ASEAN countries to coordinate a unified and firm response. ASEAN’s Convention Against Trafficking in Persons (ACTIP), which entered into force in 2016, is not enough due to its weak implementation. ASEAN has a principle of non-intervention. Similar to international law, any ASEAN implementation is permissible. Most ASEAN countries are focused on domestic actions rather than regional cooperation, which has led to difficulty in addressing all forms of human trafficking. In 2025, China and Thailand have done crackdowns in Myanmar and Cambodia. The United States and United Kingdom have imposed sanctions on the Prince group, who are alleged to be running scam networks worldwide. The United States has also seized $15 billion in funds from Chen Zhi, founder of the Prince Group, and US federal prosecutors have indicted him. If unchecked, these criminal networks could exacerbate instability, deepen leverage for regional rivals like China, and threaten the delicate balance of power in the Indo-Pacific.

South Korea, India, and China have actively engaged in repatriating their citizens from trafficking and scam operations in Southeast Asia, reflecting heightened awareness of the human trafficking crisis. For instance, China has repatriated thousands of victims trafficked to scam centers in Myanmar and neighboring countries amid a broader crackdown on illicit casinos and cyber scams. South Korea has collaborated with regional governments to rescue and return victims exploited in these networks. India has likewise undertaken repatriation efforts for its nationals trapped in human trafficking rings across Southeast Asia.

However, Southeast Asia’s permissive political and enforcement environment, particularly in countries like Thailand and Malaysia, which remains a major transit and destination hub, continues to allow human trafficking rings to operate with relative impunity. Corruption and weak rule of law exacerbate the problem, underscoring the critical need for stronger coordinated regional efforts and reforms to disrupt these entrenched trafficking networks.

The rapid growth of scam centers in Southeast Asia poses an urgent threat to the region’s political stability and economic future. ASEAN must move beyond rhetoric and take decisive, coordinated action. This includes stronger anti-corruption reforms, enhanced law enforcement cooperation, and targeted sanctions against those enabling these illicit networks. Given that scam centers now account for a significant portion of Cambodia’s GDP, economic diversification is critical to reduce dependence on illegal activities. Failure to act decisively will allow criminal impunity to flourish, damaging Southeast Asia’s relations with major partners like China, India, and South Korea, while also undermining Southeast Asia’s long-term security and prosperity. The time for persistent inaction has passed.

A unified ASEAN-led crackdown is essential to protect the region’s future stability. If the issue is not addressed within ASEAN, there is the risk that it then becomes a greater international issue. The United States and the United Kingdom have already put sanctions against a Cambodian based company exposed for running scam operations. US citizens lost $16.6 billion in south east Asian scam operations in 2024. Although the reach is currently global, any more growth would impact western countries which will ultimately lead to western intervention in Southeast Asia. In an effort to maintain sovereignty within the region, ASEAN must act together and boldly to crack down on scam centers.

***Tierra Monique Sydnor is post-graduate in French Studies from New York University. The views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of Kalinga Institute of Indo-Pacific Studies.