By Niranjana R

Every year, families flee rising waters. Cities crumble under storms. Crops vanish, and millions are displaced. The age of climate complacency is over. In the Indo-Pacific, a region of dense populations, sharp geopolitical rivalries, and fragile ecosystems, climate change acts as a security multiplier. It rarely sparks conflict directly, but it amplifies existing tensions, turning small disputes into potential flashpoints. From Bangladesh’s flooded deltas to Pacific islands on the brink of extinction, the human toll is immediate and severe: rising seas threaten entire homelands, force mass migration, and push regional security systems to the breaking point.

This article looks at how climate change acts as a security multiplier across the Indo-Pacific. Rising seas, storm surges, floods, droughts, heatwaves, coastal erosion, and dwindling fisheries destroy livelihoods, forced migration, and deepen social, economic, and geopolitical vulnerabilities. Regional and global actors - groupings like QUAD and AUKUS - are responding strategically and diplomatically, while efforts in policy, resilience-building, and cooperative security aim to turn climate pressures into coordinated action rather than cascading crises.

Climate Change as a Security Multiplier

Climate change acts as a “security multiplier” (also called a threat multiplier), quietly magnifying risks across society, governance, and regional security. It may not ignite conflict on its own, but it intensifies pre-existing vulnerabilities across multiple dimensions. Shrinking freshwater supplies and declining arable land can fuel resource scarcity and competition, sparking disputes over water, fisheries, or agriculture, even between neighbouring states, thereby heightening security risks. Floods, cyclones, and rising seas force migration, strain urban centres, and overwhelm governance systems. Livelihoods are stripped away, states struggle, and communities are exposed. When governments fail to protect citizens, political fragility rises, protests erupt, and tensions escalate. In essence, climate change does not start the fire - it fans it, transforming slow-onset environmental stress into cascading crises that ripple across society, governance, and international relations.

Regional Impacts in the Indo-Pacific

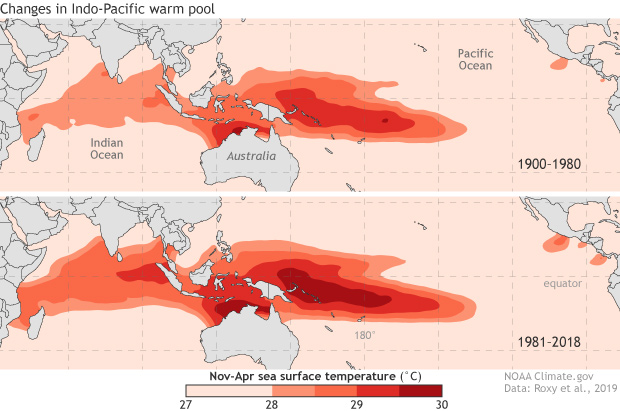

Across the Indo-Pacific, climate change is reshaping power, security, and livelihoods simultaneously. In South Asia, countries like Bangladesh and India brace for relentless cyclones, riverine floods, and accelerating coastal erosion. In Bangladesh’s low-lying delta, rising seas and saltwater intrusion threaten farmland, freshwater, and livelihoods, forcing migration and fuelling social unrest. Shared water systems, like the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin, intensify political and social tensions, revealing how environmental stress intersects with human governance.

Southeast Asia faces its own escalating challenges. Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia battle typhoons, droughts, and creeping coastal inundation. Jakarta’s sinking neighbourhoods highlight the vulnerabilities of densely packed urban populations, while dwindling fish stocks and rising waters in the South China Sea feed maritime disputes, turning ecological change into strategic friction.

In the Pacific, island nations such as Tuvalu, Kiribati, and Marshall confront existential threats. Rising seas jeopardize sovereignty, force communities to relocate, and strain international humanitarian and diplomatic frameworks. Limited adaptive capacity heightens dependence on regional and global partners, even as communities struggle to sustain their livelihoods.

Responses by Regional and Global Actors

Governments and multilateral organizations increasingly recognise climate change as a critical security challenge, blending adaptation, diplomacy, and strategic planning. The United Nations Development Programme’s Climate Security Project helps vulnerable island nations manage water stress, migration, and disasters, while the Pacific Islands Forum’s ‘Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific’, coordinates resilience, resource-sharing, and disaster preparedness across South and Southeast Asia. The Kainaki II Declaration names climate change a security threat, and think tanks such as International Military Council on Climate and Security map rising seas and resource pressures to guide policy and strategic alliances.

Regional cooperation remains key: the Pacific Islands Forum drives climate advocacy and resilience-building, while South and Southeast Asian nations have set up disaster response mechanisms, though uneven capacity leaves some populations exposed. Strategic groupings like QUAD and AUKUS are integrating climate resilience into security dialogues, recognising that rising seas, storms, and resource pressures can disrupt trade, infrastructure, and maritime security. Meanwhile, governments invest in coastal defences, early-warning systems, and climate-resilient infrastructure, using migration management and disaster diplomacy to prevent humanitarian crises from escalating into broader security threats.

Yet gaps remain - climate and security are often treated separately, constraining smaller states’ adaptive capacity, while geopolitical rivalries can overshadow cooperation.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

Stability in the Indo-Pacific increasingly hinges on recognising climate change as a core security concern. Security agencies must adopt integrated climate-security planning, factoring climate scenarios into strategic assessments and anticipating how environmental stress could amplify conflict risks.

Regional cooperation is critical. Platforms like the Pacific Islands Forum, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation should strengthen coordination on climate resilience, disaster response, and resource-sharing to prevent local crises from escalating into wider instability.

Enhancing adaptive capacity cannot be overlooked. Investments in resilient infrastructure, disaster management, and urban planning are vital, especially for coastal and island communities vulnerable to rising seas and extreme weather events.

Finally, Diplomatic and strategic frameworks like QUAD and AUKUS must weave climate and humanitarian priorities into their security objectives, supporting both mitigation and adaptation efforts across partner states.

Taken together, these measures can transform climate change from a destabilizing threat into a catalyst for cooperative security, reinforcing resilience and safeguarding regional stability.

Conclusion

Climate change in the Indo-Pacific is more than an environmental challenge - it is a strategic reality that shapes power, security, and human survival. Its impacts are no longer hypothetical. Slow-onset stresses and extreme events collide with governance, economies, and societies, exposing gaps in preparedness and cooperation. Addressing these pressures demands bold, coordinated action: integrating climate into security planning, strengthening regional and international cooperation, building resilient infrastructure, and embedding humanitarian and mitigation priorities into strategic frameworks. Only by recognising climate change as a core security multiplier can states and alliances turn risk into opportunity - forging resilience, reinforcing stability, and securing a future where societies and nations alike can withstand the shocks of a warming world. In the Indo-Pacific, inaction is not an option.

**Niranjana R is a postgraduate in Political Science and International Relations from IGNOU, and Public Policy from OP Jindal Global University. The views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of Kalinga Institute of Indo-Pacific Studies.